Designing for Scientists

Microbiology lab

In the Department of Natural Science at California State University San Bernardino, there's a tiny lab doing big things. With funding from NASA & NIS, a dozen scientists are researching extremophile archaea (microbes) to uncover the origins of humanity.

Seraph

My duty was to design software tools, hardware equipment, and the entire lab itself. The challenge was to improve the UX and efficiency of expensive custom-built bleeding-edge systems used by our own scientists.

Every project had different teams. I worked with engineers, chemists, carpenters, biophysicists and some other ists. I was the only designer.

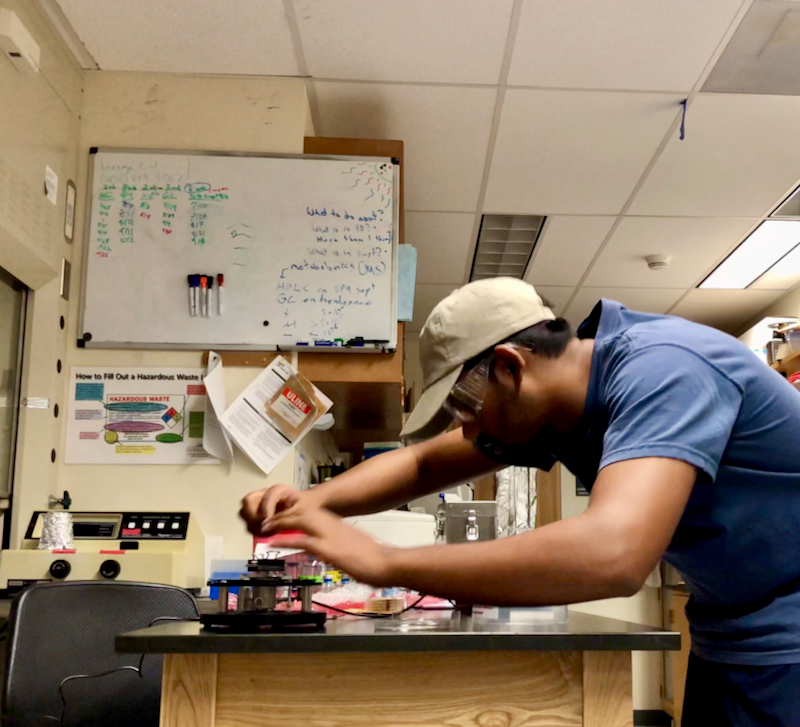

Becoming the user

I had to deliver fast. Which meant I had to understand my brilliant users and their dense ever-evolving intricate work fast. Card-sorting sessions just weren't going to cut it. It only made sense for me to work as a scientist so that I could efficiently learn what I needed to.

And hey, I could finally put my expensive Bioinformatics degree to use.

Researching the researchers

One of my favorite ways to understand users is to have them teach and demonstrate their work to me (aka contextual inquiry). When my users taught me how to work alongside them on their research, they revealed the inner workings of their minds. Asking neutral questions on how to use tools can easily get them to open up about their pain-points.

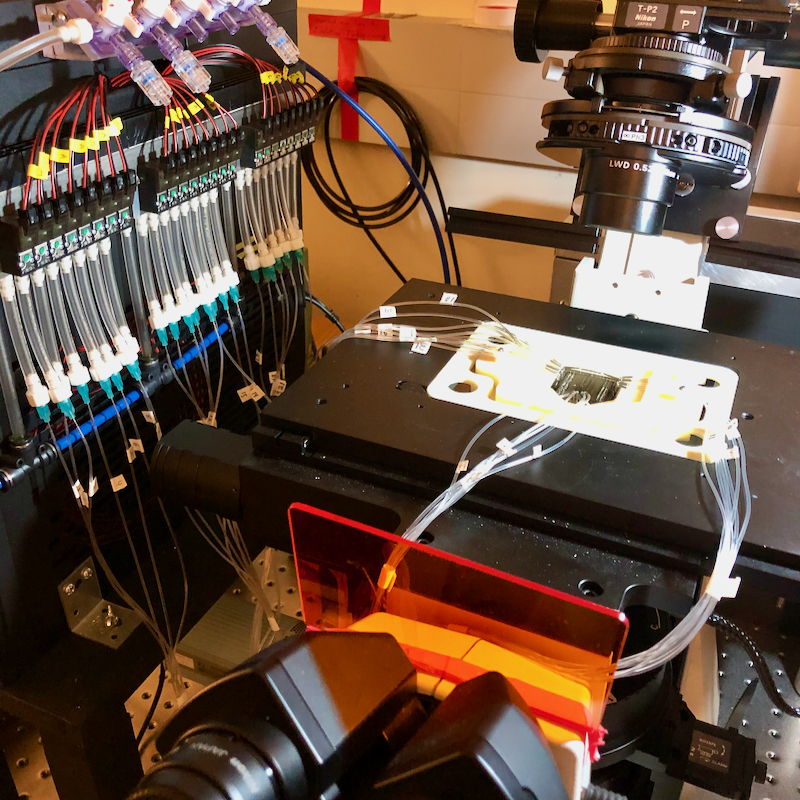

The scientists' understanding of their tools was limited. If I asked them to explain the organs of our cell-sorting system, they'd respond "I don't know". This was an issue.

Killing spirits

You would not believe how often equipment breaks down at the lab. That's the curse of high-tech custom-built tools.

It's on scientists to fix their tools fast and get on with their research. Or else their fussy microbes will die, wasting months of work and thousands in funding. It's high stakes. I've seen my users furiously bang on keyboards, moan in pain, and look down in despair when their tools break. How can they fix things they don't understand?

Say hi to my reflection!

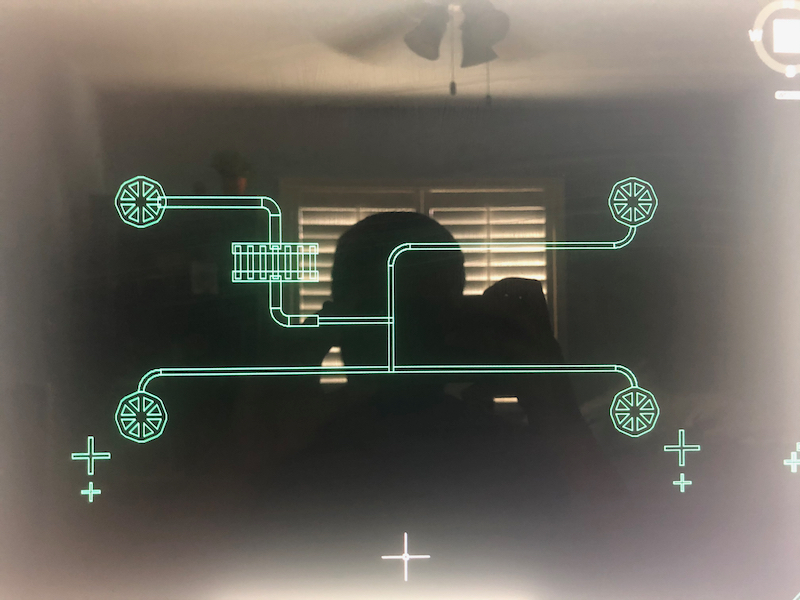

Transparency

Luckily, I watch anime. An amazing sci-fi show called Neon Genesis Evangelion gave me the answer on a silver platter. Technology in this show had self-explanatory designs. The inner-workings are laid out in diagrams, and status changes are communicated by interesting animations. This is done so that the audience can understand how sci-fi tech works in a split-second.

Consider this

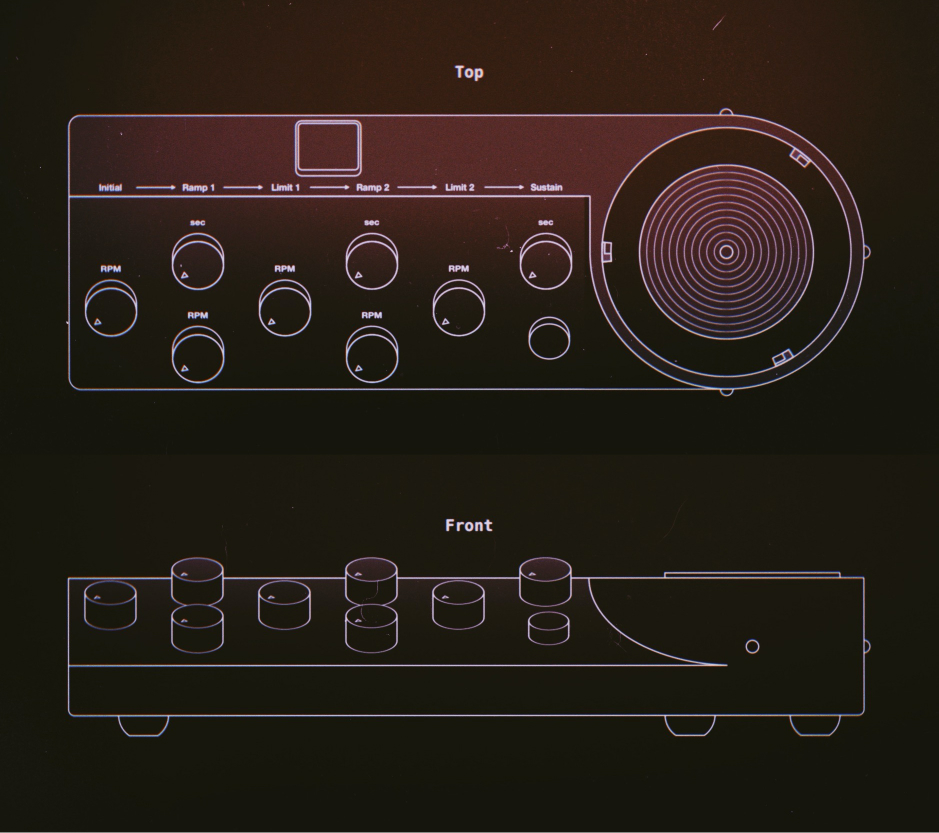

Implementing a philosophy of show & tell was difficult. Turning high-tech system guts into a digestible diagram took a lot of research and head-scratching. I had to account for:

- User's location in the lab relative to the equipment.

- Placement of the tools in the lab.

- Equipment that wasn't willing to communicate its status.

- Not just how a tool works immediately, but also how it works in greater systems.

- Users with color-blindness and visual impairments.

- Power usage of the diagrams (because of inefficient hardware polling).

- The possibility that replacing parts can deprecate the design.

- Different phases of research, including preparation and clean-up.

And of course, I had to account for designing each product within a month.

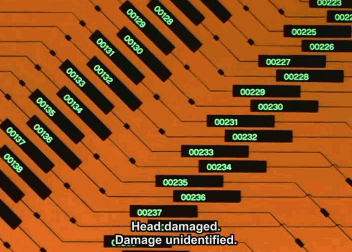

It shows that two links are disconnected.

Typical spin-coaters don't do this.

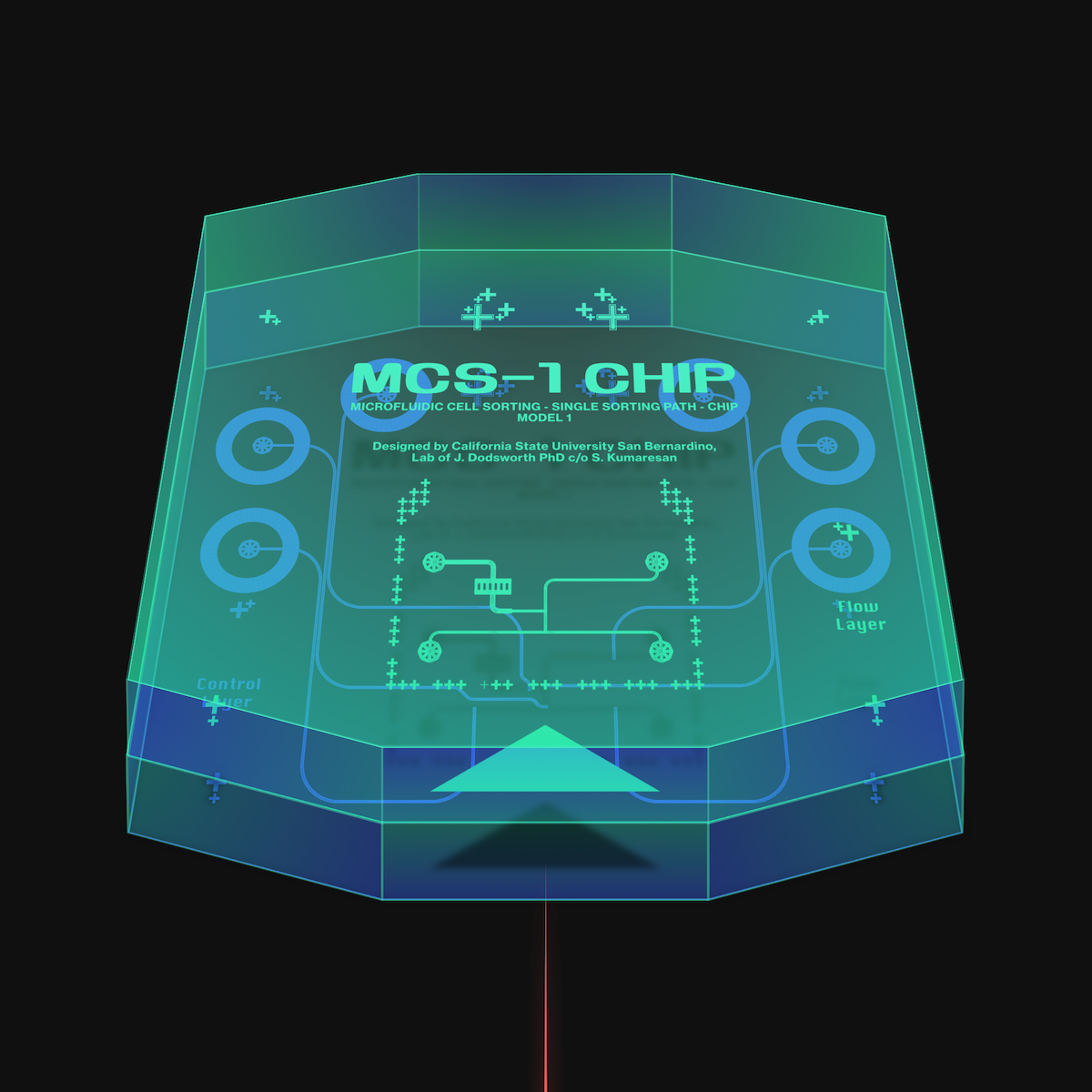

MCS-1 reduced errors by indicating faces and ports.

Good results

Our products were very successful. Once in a while, our scientists would stop by to thank me for my work. My designs were able to shave off hours of research labor. Scientists actually got to go home earlier because of me.

Single-cell sorting times were reduced by 40%. My ergonomic designs reduced hand pains and constant repositioning. Scientists could finally fix their equipment and save their microbes because of my show & tell philosophy.

Since I was delivering good results, my budget & scope increased with every project.

This one is actually deformed...

The end

Due to the pandemic, the lab went into hiatus in 2020. Thankfully, I had just designed the final tweaks in our microfluidic chips before the lab closed.

I loved working there. This page was originally a massive essay on all the things I did and learned there. I couldn't stop writing. But all good things know when to end.

Home